Bangladesh – The Adventure Begins

It is disconcerting—waking up your first morning in a strange country. Especially when it is still dark, and your wakeup call is the blaring sound of a muezzin’s voice carried over a loudspeaker from some distant minaret—announcing the day’s first adhan, or Muslim call to prayer. The call ripples across the city as it is picked up and echoed again and again by other muezzins on other minarets.

In Dhaka, as in other Muslim cities, there are five calls to prayer each day, all the same except for the first, which I learned at breakfast that morning has one extra line. Lest the believer be tempted to turn over and go back to sleep, the first call to prayer ends with a reminder that “prayer is better than sleep.” The call to prayer is central to the Muslim faith. It is not just the first thing a Muslim hears every day; it is imprinted from birth. The words of the adhan are the first words whispered into the ear of a newborn Muslim child.

I couldn’t have asked for more gracious hosts during my stay in Dhaka. Even though I was there for the Presbyterian Church, the people at the Baptist mission house did everything they could to make me comfortable and be helpful. They generously took the time to provide me with what proved to be critical information about Dhaka and the Bengali people. I had done my homework, read books and government reports to prepare myself to work within the Muslim and Hindu communities around Dhaka, but there is no substitute for the kind of firsthand information one can only get from people who have lived and worked in an area. It is always the little things, the nuances that are never documented in the literature, that enable you to cross cultural barriers and win the trust of the people who view you as an outsider, and in the case of Muslims, even more critical…as a nonbeliever.

I had the sense that the Baptist missionaries were treating me with deference. This, I attributed to the fact that I was on the film crew. It wasn’t until I got back to the States that I found out it was not my profession, but my religion that made me special in their eyes. Although it was never mentioned, my Baptist hosts had been informed that I was Jewish, a fact that made me an exotic in their world.

One reaction to my faith I found particularly endearing. While I wasn’t conscious of it while I was there, in deference to my being Jewish my hosts adjusted their eating habits during my stay. No pork, ham or bacon was served for the duration of my visit which, in a way, was a pity. I am not a big fan of pork (except in Chinese food) or ham, but I would have had no problem if they had served these foods, and I would have loved a little bacon with my eggs at breakfast. Still, in hindsight, I appreciate their thoughtfulness.

|

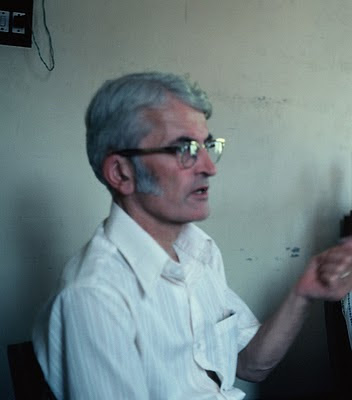

| Dr. Herb Coddington, Medical Missionary for the Presbyterian Church, U.S. in Bangladesh |

|

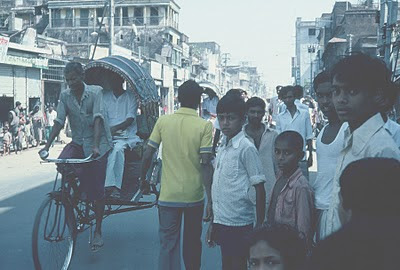

| The bustling streets of Dhaka |

DR. CODDINGTON’S DREAM

When Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) was being born out of Pakistan’s bloody civil war in the early 1970’s, Dr. Herb Coddington was miles away in Korea, heading up a tuberculosis clinic. Bangladesh was not even on his radar—until he began having a recurring dream. In the dream he was instructed by God to go to Bangladesh because he was needed there. After having the dream a few times the doctor decided he was being called to act, and asked his church to send him to Bangladesh.

The Presbyterian Church considered his request. They judiciously analyzed the situation in the new country. The war, plus two consecutive disastrous monsoon seasons had left Bangladesh politically unstable and economically in shambles. Millions had died in these events, crops had been destroyed, and a major part of the population was displaced and struggling for survival. After a survey of Church resources, the Church reached the realistic conclusion that what little they could invest in Bangladesh would make no real difference in the struggling nation. They turned Dr. Coddington down.

The dream persisted. When it came time for his vacation, instead of returning to the States, Dr. Coddington went to Bangladesh. When the ecumenical Christian community discovered he was a tuberculosis expert, a disease that was rampant in Bangladesh, they petitioned the Presbyterian Church for his services…a request the Church could not deny.

The Presbyterian Church agreed to let Dr. Coddington move to Bangladesh—with one caveat: he was only to work in the hospital as a tuberculosis expert. There would be no monies forthcoming for any other work, and he was instructed not to involve himself in any other medical activities. But a man of deep faith and conscience, Dr. Coddington could not turn his back on need. So a simple act of grace turned into an unauthorized weekly early morning clinic for the neighborhood poor, and a witnessed government act of intolerance and cruelty prompted a reaction that gave birth to an ecumenical outreach that would bring homes and hope to thousands of displaced Bengalis.

NEXT: THE MIRACLE AT TONGEE