It was apparent, as I struggled to teach, rear my daughter, and pursue my master’s degree that, in spite of Dr. Christiansen’s encouragement, I would never be able to muster the money or the stamina to go on and get my doctorate. That left me with only one more year at the University of Florida. It was time to start job hunting.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Communication Department was looking for a staff writer with documentary film experience. With a solid recommendation from the man I had worked with on the state's water lily project, I applied and got the job. It meant moving to Washington, D.C., but the salary and benefits offered something I had not known in my adult life: financial stability. My new boss even had a project waiting for me, a documentary on the invasion of killer bees from Latin America. They weren’t here yet, but the Agriculture Department wanted to warn the nation’s farmers about the prospective danger. I told Dr. Christiansen I would be leaving at the end of the semester. He was sorry to see me go, but wished me the best of luck.

After procrastinating as long as I could, I was about to break the news to my daughter that we were going to move again when I received a phone call from my new boss. President Ford had just put a hiring freeze on all federal agencies. My job was put on hold...indefinitely. I was back at square one.

Looking back, the remarkable thing about my life has been that whenever I believed I had run out of options something unexpected, some solution that was far better than any I could have imagined, appeared in my life. This time it came in the form of a phone call from a producer I had only worked for once, back in 1972. It was on a project for the Presbyterian Church U.S. (see my series of postings on my 1972 trip to Brazil)...my first overseas assignment.

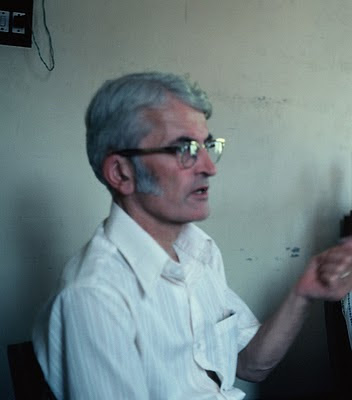

I don’t know how Sandy MacDonnell tracked me down, but he had a new project for the Presbyterian Church, this time in Bangladesh, and he wanted me onboard as the writer. Hallelujah! I was back in the film business...that is, if Dr. Christiansen would give me permission to go.

The fact that the shoot was scheduled for the summer, a time when the class load wasn’t very large, was a plus. Still, had no idea of how Dr. Christiansen would react to my request. Again, luck was on my side. Dr. Christiansen, I learned, loved India. He had spent two years there on a communications research project when Bangladesh was still part of that country and had wonderful memories of the place and the people. “Of course you should go!” he said. He would figure a way to work it out. I think he was as excited about the prospect of my going as I was. He was filled with advice about what to take and what to see.

There was, of course, Eileen to consider. I would be away at least three weeks. “I’ll look after her,” my housemate, Pat Holmes, said when I told her about the job. “Don’t worry about a thing.” That left just one more hurdle to overcome... a big one.

Documentary writers incur expenses. They may be reimbursable, but the procedure is for the writer to put whatever they spend for the job on a credit card, then turn in their receipts and a record of the expenses to get reimbursed. The problem was... I didn’t have a credit card. All the credit cards I had were in my ex-husband’s name and requests to have them put in my name had been turned down. I was told I had to build up a credit history before I could get a credit card.

I went to my bank in Gainesville to try again. Surely, now that I had a steady job with the University, and had established a residence and a record the past two years of paying all my bills on time they wouldn’t turn me down. But once again I hit a brick wall. None of this mattered because I had no credit history. I hadn’t bought anything on time, paid off a loan, or done anything that left a paper trail. It didn’t matter that I had been the primary breadwinner for a major part of my life, or that the only reason my ex-husband's credit cards got paid was because I provided much of the money to pay them. The bank saw me as a credit risk because I had not incurred visible debt that they could evaluate.

The banker feigned sympathy, but said there was nothing he could do. I left the his office in total despair, struggling to hold back my tears. No credit card meant no job. I got as far as the front door. That’s when it hit me! My frustration gave way to a burning anger. Not usually one to seek confrontation, I suddenly found myself hungering for it. I turned around and marched back to the banker’s office.

“Ms. Fader!” There was alarm in the man's voice as he rose from his chair.

“I need this credit card.” I announced. “I have to have it. I can’t take this assignment without it.”

“I would really like to help you out,” he said, regaining his composure, “but, as I explained, my hands are tied. You have no credit history.”

“My students, the ones your bank has been so actively soliciting... the ones you have been handing out credit cards to without blinking an eye...the young men and women who have never held a job, probably never paid a bill,...are you going to tell me they have a credit history?”

“Well no, but that is different. They...”

“.... and if my ex-husband walked in here today, with his questionable credit history, you would have no trouble issuing him a credit card, would you?”

“Well, I don’t know about that, Mrs. Fader," he said. "It would depend on...”

“I have a job. I have no debt. I have a history of paying my bills on time. If you cannot see fit to give me a credit card, I am afraid you give me no choice but to sue your bank.”

“Sue?”

I had hit a nerve. “Yes, sue," I said, "for.... for... sex discrimination.”

The blood drained out of the banker’s face. Twenty minutes later I walked out of the bank with my credit card. I had to settle for a $500 limit and hoped that would be enough, but at least I could take the job.”

Some years later, during a discussion I was having with my daughter about her very successful career, she said to me, “Remember, back in Gainesville, when you fought with the bank to get a credit card so you could go to Bangladesh? You were so strong, Mom, so independent. I learned it all from you.

I’m glad she was inspired, but the truth is, it wasn’t strength or independence... it was desperation. Yet, looking back, I guess that incident did mark the day I finally grew up.

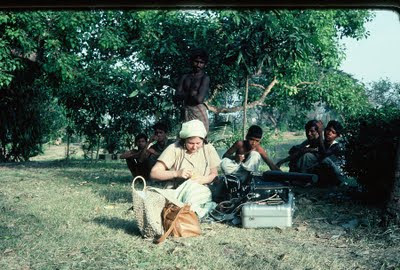

Coming next: My adventures in Bangladesh.