Easter Sunday, 1975 Dhaka, Bangladesh

I bolted upright in my bed. It wasn't a dream. The ear-piercing clamor was real. Had it finally happened—the military coup the missionaries had been talking about in hushed tones the past few days? I checked the clock. Four A.M. A hell of a time for a coup.

When I finally shook the daze of sleep from my head, I realized it wasn't artillery I was hearing; more like someone banging on large, empty metal containers or tin pans. The noise was coming from the courtyard beneath my window.

Cautiously, I pulled the curtain aside. The courtyard was dark, but I could make out the shape of a large truck. There appeared to be some figures in the open bed of the truck. They were furiously beating on what looked like oil drums and over-sized garbage can lids; pummeling them for all they were worth. The clamorous result of their efforts almost drowned out the knocking at my bedroom door.

"Sunny, are you up?"

What a question. I doubted even the dead could have slept through that racket. "Yes," I said.

"Good," the voice on the other side of the door said. "We'll be waiting for you downstairs."

And that was my introduction to the Bengali Easter custom of arousing believers for the Sunrise Service. With an unbridled sense of urgency, young men in old trucks, armed with empty oil barrels, wash basins, metal trays, and any other noisemakers they could find or devise, set out in the wee hours of Easter morning for the homes of the faithful where, with great enthusiasm, they beat and banged their makeshift instruments to call the city's scant Christian population to prayer.

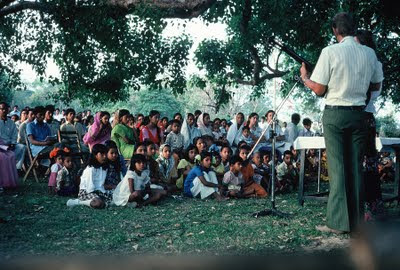

I hurriedly dressed and joined my Baptist missionary hosts and we headed for a lake side park. Easter Sunrise service in Dhaka in 1975 was not compartmentalized by denomination. It was a community affair. Communicants from all the area's Christian churches greeted the holy day together. They gathered in the dark, bringing their chairs, to wait for the sun to rise. They sang together, prayed together, and their priests and pastors shared the holy word with the ecumenical congregation.

|

| The Christian Community gathers, Easter Sunday 1975, Dhaka, Bangladesh |

And when the sun had risen, and the service had been completed, the Baptists, Presbyterians, and other denominations proceeded to the Anglican Church for the rest of the Easter day celebration. (The Anglicans, I believe, were the only denomination in the city with their own church.)

|

| Anglican Church, Dhaka, Bangladesh |

The women in their colorful saris, the men in their crisp white lungis and shirts, flowed into the sanctuary and seated themselves on woven mats on the floor. Their voices rose in song. The sacred melodies were unfamiliar, the language foreign, but the sense of holiness and celebration was unmistakable.

I have attended other Easter Sunday services, in Washington State and California, where the pageantry and service was more familiar, the language understandable and the fellowship welcoming, but none have moved me more than that Easter Sunday service in 1975 in that austere little church in Bangladesh, amidst that group of strangers whose world I barely understood. Their faith, their passion for their belief was palpable, and it moved me.

I thought about them this Easter Sunday as I read how Christians in some of the Muslim countries in the Middle East chose not to celebrate their most holy holiday this year for fear that their Muslim neighbors would kill them. That small group of Christians in Bangladesh knew that fear. They had felt the wrath of their Muslim neighbors during the revolution, as did the Hindu citizens of Bangladesh. All was calm at the moment, but in such countries, where political instability exists and poverty is rampant, the possibility of mayhem is ever present.

Christian, Jew, Muslim... it is never easy to be a minority, to hold a belief that is out of step with the majority of the people around you. Sadly, it is no different in this country. When things are not going well, it is too easy to target and blame the “other” for our discontent, to make them a scapegoat for our problems. Even good people sometimes fall into that trap.

Let me pose a question. Christian, Jew, Muslim... all believe in one God. All these religions teach that God created all things. Then by what distorted logic can anyone professing to be a Christian, Jew or Moslem, anyone claiming to love God, justify killing, or even hating a fellow human being—another creature lovingly created by God? Just something for you to ponder.

NEXT: THE CREW ARRIVES

Thank you for your personal story, Sunny. Your words, "The sacred melodies were unfamiliar, the language foreign, but the sense of holiness and celebration was unmistakable", remind us of the spiritual connectivity of all humans - and of our natural receptivity to that indescribable sense which Jung termed "The Oversoul".

ReplyDeleteAs we go through life, we seem to become more open to the ineffability of the spiritual "world". On that journey, many leave old dogmatic religions and gradually discover unique, authentic and more peaceful ways of being. Sometimes not understanding the language helps!

Donna

http://organistchoirdirector.blogspot.com

If we can find in ourselves the same violence that we fear or disdain in other people or places, we will not judge others so harshly, even those who are violent. We will begin the process of creating a world without violence, or at least with less violence. Until then, we will contribute to the violence in the world not reduce it. I loved this Easter celebration, thanks. ( Comment paraphrased from Gary Zukov Soul to Soul that I was reading just before I read this) Martha Bennett

ReplyDelete