The country was barely three years old when I arrived there in 1975 to work on a documentary. Signs of the high price Bangladesh had paid for its independence were everywhere. I saw it in the gaunt, weary faces of the refugees at Tongee; in the rampant poverty and the war-scarred, deserted buildings strewn throughout the countryside; in the inordinate number of widows and orphans we found everywhere we went. But it was not until I watched and read the BBC retrospective last week on the birth of Bangladesh that I fully grasped the scope of the tragedy that occurred when the breach between East and West Pakistan erupted into war, and the two disparate areas, forcibly bonded into a single nation for political and religious reasons, were torn apart. Given our nation's current relationship with Pakistan, I think it is instructive to look back at what happened in that region 40 years ago, and the role our nation played (or didn't play) in this shameful piece of history.

From the very beginning, the partitioning by the British of the Punjab and Bengal regions of India into the single nation of West and East Pakistan was ill-conceived. The logic for the creation of Pakistan, from the British perspective, was this: It was clear that Hindus and Muslims would never get along, so the only way to insure the successful transition of India to an independent, self-governing part of the Empire was to partition the overwhelmingly Muslim areas of the country into a separate nation.

|

| Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan, is primarily an agrarian society, and was easily manipulated and controlled by the more industrialized West Pakistan. |

It is not surprising, therefore, that West Pakistan was quickly able to amass the majority of the political power in the new nation. And since East Pakistan had to depend on West Pakistan to process its major crop, jute, it did not take West Pakistan long to gain control of East Pakistan's agricultural output. As one man told me during my visit, West Pakistan used East Pakistan as its bread basket and, in his words, “raped the region of its resources.” As a result, West Pakistan grew richer while East Pakistan grew poorer.

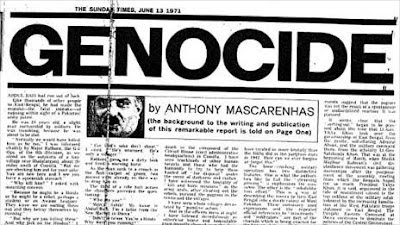

At a meeting of the military top brass, General Agha Mohammed Yahya Khan set the tone of the campaign. "Kill three million of them and the rest will eat out of our hands," he told the group. On March 25th, 1971, the Pakistan army, with the support of political and religious militias, unleashed Operation Searchlight on East Pakistan. Bengali members of the military services were disarmed and killed and students and the intelligentsia systematically liquidated. Able-bodied Bengali males were picked up and gunned down. In the six months that followed General Yahay Khan's goal was reached, at least according to Bangladeshi authorities who say that during the one-sided war three million people were killed. (The Pakistanis contest that number, placing the figure at closer to 200,000.)

I was on my way to Tongee with Dr. Coddington when we passed an obviously once grand building in ruins. I asked Dr. Coddington what it was. He said it has been the home and hospital of a much beloved Hindu doctor who used to serve the area—Hindus and Muslims alike. One night, during the madness of the war, Dr. Coddington said, a gang of Bengali Muslims attacked the building and brutally slaughtered the doctor, his family, and the hospital staff. The irony of this tragedy is that in feeding their irrational hatred of Hindus, these men deprived themselves and all the other people in the area of a caring, compassionate doctor and the only medical care available in the region.

But back to the war. West Pakistan failed to gather international support, and found itself fighting a lone battle with only the United States providing any external help. (The United States and China were the only two Countries that supported West Pakistan.) Still, with little substantive resistance from the defenseless population of East Pakistan it looked as though nothing could stop the aggressors.

As the war continued, eight to ten million Bengali refugees fled to India. Alarmed by the massive influx of refugees, India decided to enter the war, but it was not until the Pakistani Air Force made a preemptive attack on Indian forces that Indian troops finally crossed the border. Suddenly the Pakistani army found itself being attacked from the east by the Indian army, the north and east by guerrillas, and from all quarters by East Pakistan's civilian population. Once India entered the war, it was all over in eleven days, and the world's 139th country officially came into existence. It is interesting to note that the only objection came from China...and that while the United States finally recognized the new nation, it was the last country to do so.

Forty years later the scars of that war are still raw. A few years ago another mass grave was found, rekindling the anger in Bangladesh towards Pakistan and the people in their own country who have failed to pursue justice for the millions killed and maimed in what most of the world, albeit many with reluctance, admit was a genocide.

As for our country, forty years ago, fully aware of the genocide that was taking place, our government chose to make an expedient rather than moral decision on what should be done. It was not the first time, nor the last time we acted in such a manner, but given our complex relation with Pakistan over the past forty years, I wonder if those responsible for that decision would still feel it was justified. My brother says that I am not a realist. The world just doesn't work the way I would like it to. He is probably right. But I keep hoping that some day this country which I dearly love will grow up, and become the kind of nation most of its citizens think it is.

Thanks for an enlightening and fascinating history lesson!

ReplyDelete